Everyone knows that Nigeria’s decrepit grid is an extraordinary impediment to the private sector’s development. But, the toll inflicted on business owners is more than meets the eye.

Every evening at 6pm, a fleet of white Toyota coaster buses pulls up to two austere buildings dwarfing a back street in Victoria Island. A group of women, dressed in brightly colored blouses and tailored pants, stream out of the gated compound.

Were it not for the small Glo sign at the gate, one would have to guess what was inside the two stark buildings, their only decoration being marble columns. It is on this nondescript side street that Glo, a large telecoms company, houses its data and call centers.

The call centers are the center of the universe for this tiny slice of Lagos’ business district. Two street food vendors sell Indomie noodles, sandwiches, and boiled eggs from a makeshift table. An elderly woman sits on a blanket next to the main gate, displaying her wares (bananas and peanuts) for sale. From the back seat of a red station wagon, an enterprising business woman waits to entice a client with Ankara fabrics and shoes.

They all compete to grab the attention of the call center employees waiting to board the buses.

In addition to creating a mini informal economy, the call centers dominate this small corner of Victoria Island in another way.

Giant diesel generators that power the energy-hungry data and call centers assault the senses. Two generators, housed in large blue and white containers emblazoned with big letters ‘SDMO’, produce 2,000 kVA of electricity each — enough to power 500 houses. All day long, they emit a low rumbling sound that reverberates down the street. The exhaust pipes, recalling early industrial revolution smokestacks, belch clouds of exhaust and fill the air with an acrid smell.

Glo has no choice but to supply its own power; Nigeria doesn’t produce enough electricity.

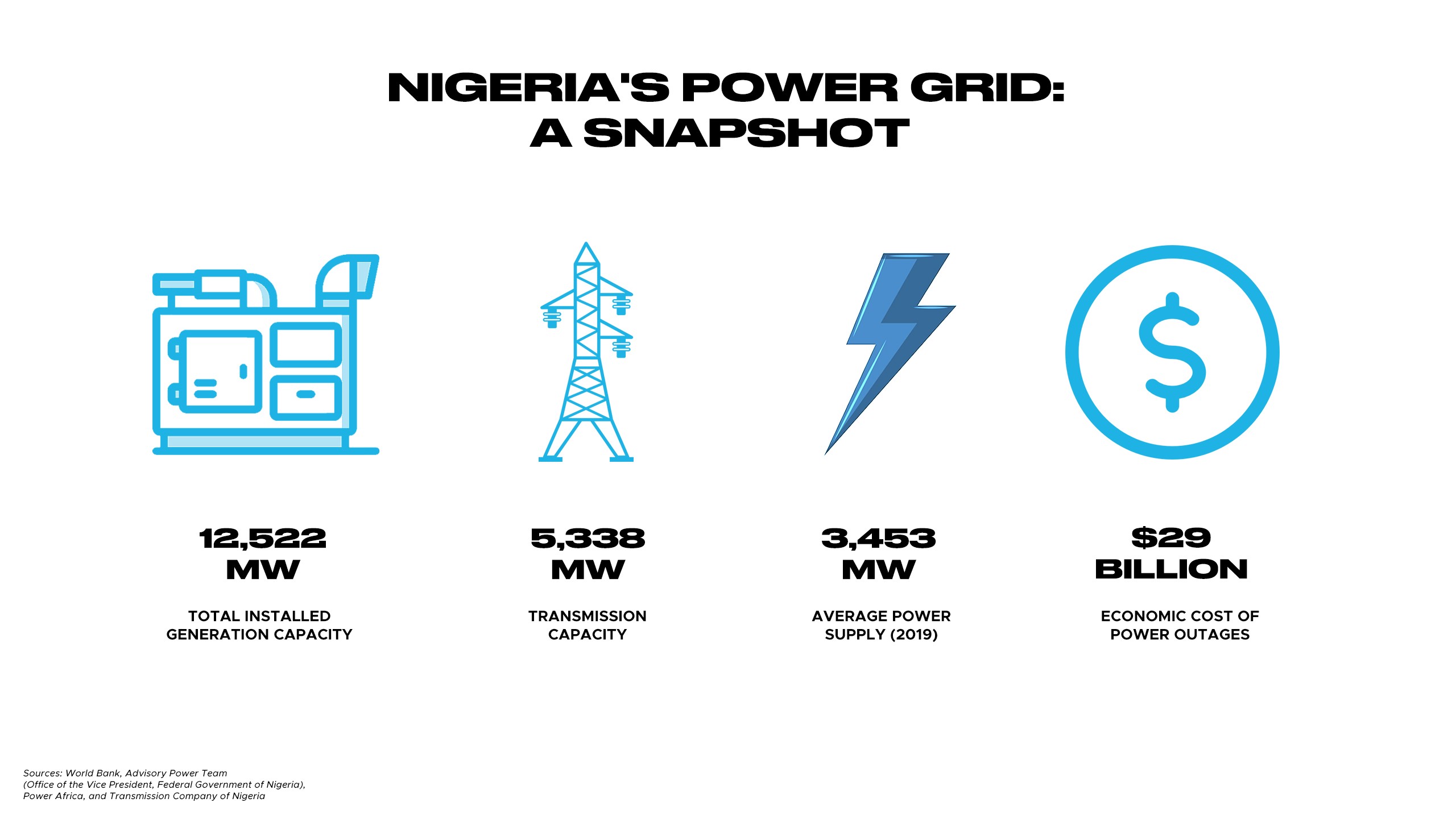

Nigeria’s power deficit is a well-known paradox. Although Nigeria is Africa’s largest economy, rich in oil and gas, it has struggled to boost its electricity supply since independence in 1960. Nigeria’s grid has a total generation capacity of 12,522 MW but it only manages to deliver 4,000–5,000 MW. Some estimates are even lower.

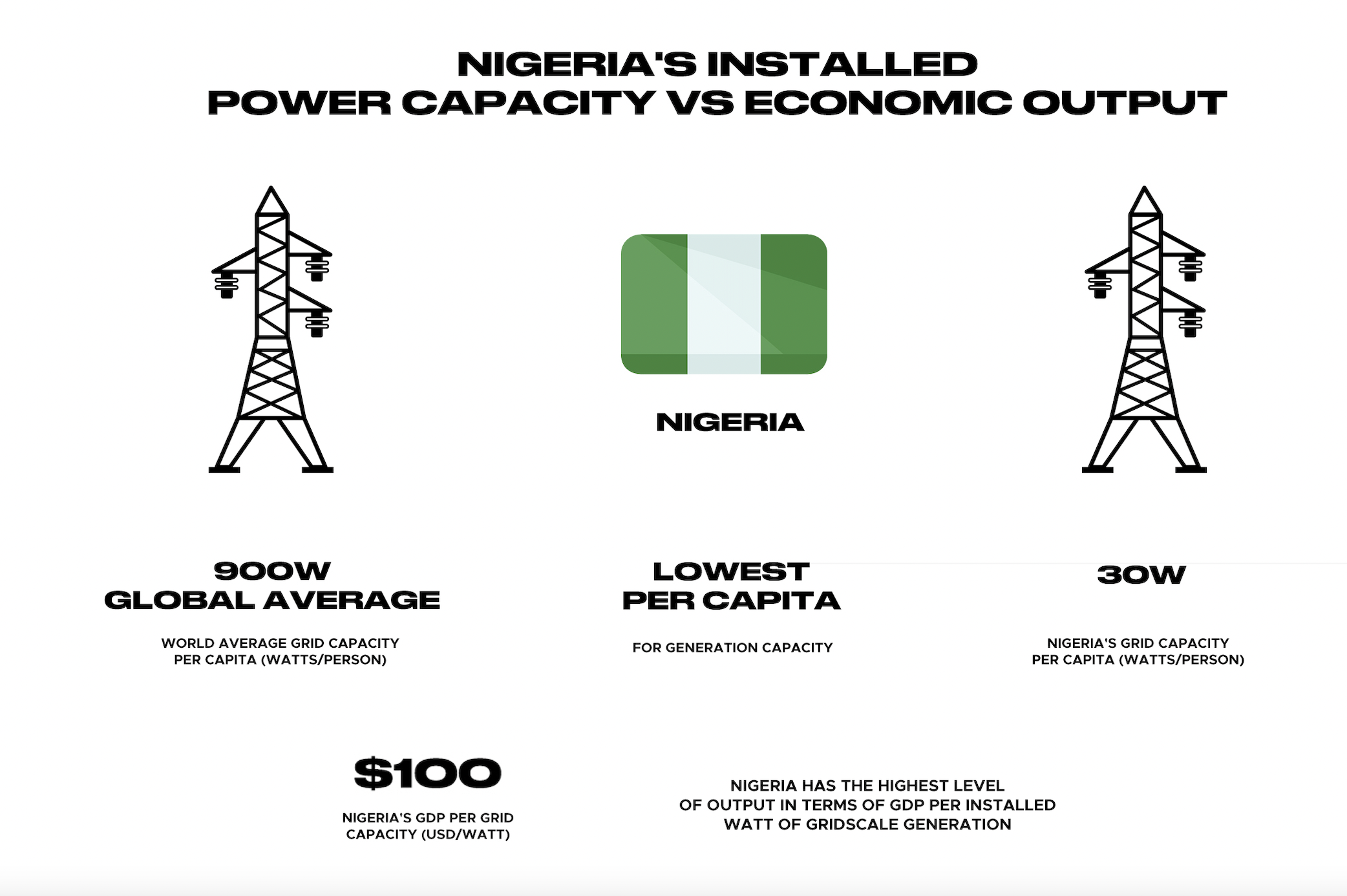

Despite having Sub-Saharan Africa’s largest population (200 million) and economy ($1.1 GDP PPP), Nigeria’s large-scale power stations produce only 5.3GW of grid electricity. That is a mere 10% of the power generation capacity of South Africa — a country with a third of the population (55 million) and smaller economy ($0.767 trillion GDP PPP adjusted).

According to a report from PwC, Nigeria should produce around 200,000 MW (200 GW) given its size. (This is based on a common industry metric that for every one million people, an industrialized country needs 1,000 MW of electricity.)

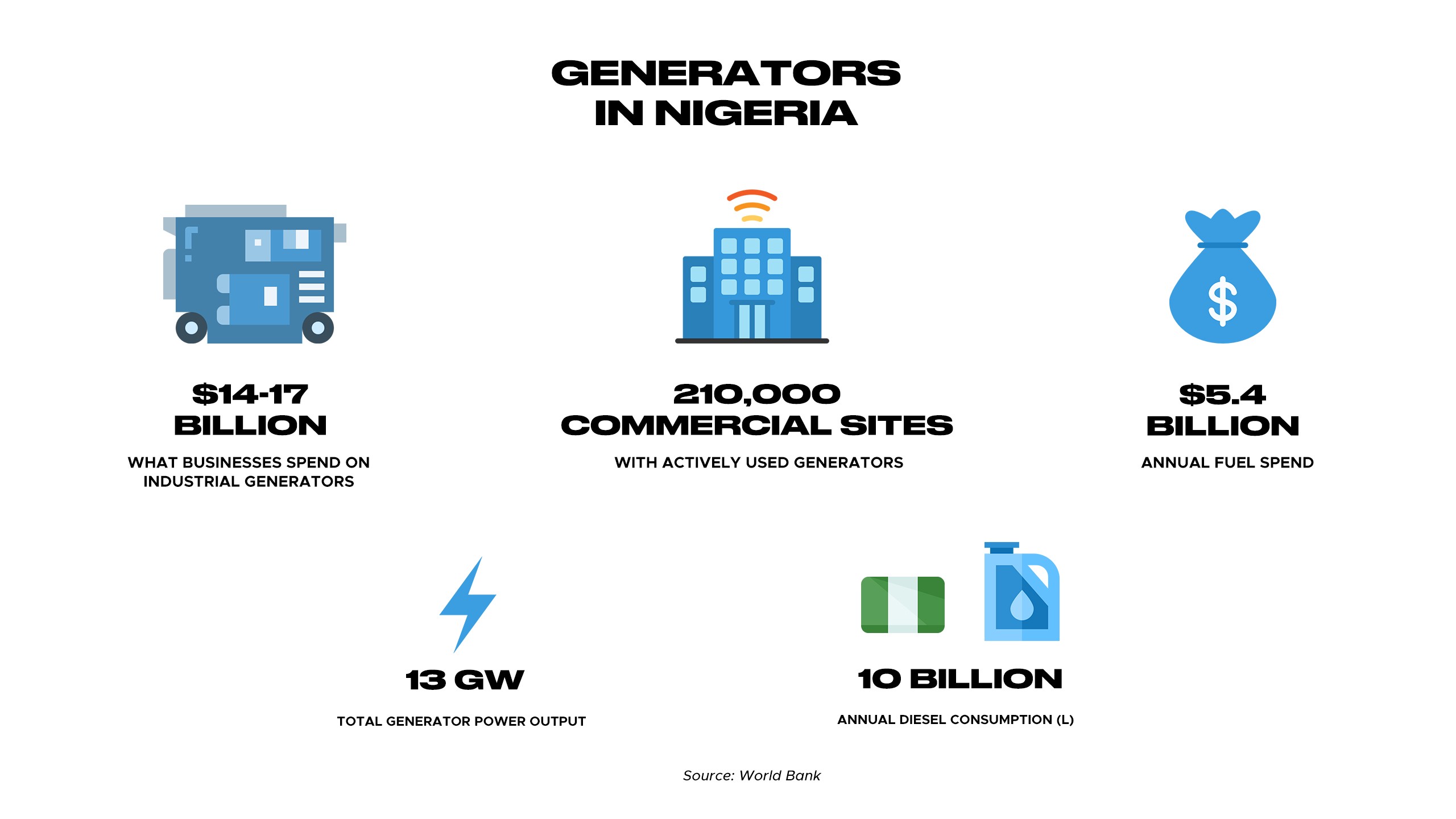

Faced with an undependable grid, Nigerians businesses are forced to provide their own electricity using diesel generators.

It is common knowledge that the chronic power shortage is an extraordinary impediment to the development and growth of Nigeria’s private sector. The lack of a working grid leads to high financial costs. When businesses add up the hidden expenses — the generator’s depreciation, maintenance, and personnel — the total cost of electricity generated by a diesel generator can go as high as 120 naira/kWhr. That is more than twice what a business pays for grid power (40 naira/kWhr).

But, the toll inflicted on business owners is more than meets the eye. For businesses and manufacturers, generating your own electricity that meets specific specs at a viable price is a burden that goes beyond what the “Ease of Doing Business” reports say.

When Nigerian business owners buy and maintain their power infrastructure, they have to juggle and stave off numerous potential problems. Business owners, especially those just starting out, often make trade-offs between the generators they can afford and possible reliability and efficiency issues.

This forces Nigerian businesses into a high wire act. They need to build a power set-up that is tailored to their needs, reliable and has good electricity quality (i.e. steady voltage and no network disturbances).

They must negotiate these moving parts while trying to drive down costs and turn a profit — the raison d’etre of any business.

The Catfish Farm: The Potential High-Stakes of Powering an Energy Intensive Business with Generators

Epe, a town of 200,000 people, is a two-hour drive from Lagos. It sits at the junction of the Lekki and Lagos lagoons, and is famous for its abundance of fish and seafood. At the 400-year-old Oluwo fish market, women fishmongers sell an assortment of fish: catfish, barracuda, red snapper, eja osa (the prized knife fish given as a dowry gift in traditional Yoruba weddings).

With its fresh water resources and proximity to Lagos, Epe is an ideal location for a fish farm, but it has a major downside: it lacks constant grid power. Electricity is so infrequent that many don’t even consider Epe to be on the grid.

In 2014, when a group of Nigerian and Israeli entrepreneurs came to Epe to set up Shaldag, an intensive aquaculture farm, they didn’t plug into the grid. Power was so scare that it didn’t make sense. They relied on diesel generators. Not only did the farm’s dependency on self-generation stifle its long-term growth, any prolonged power cuts from a fiddly generator would lead to catastrophic consequences for the business.

In the quiet town of Odo-Temu, Shaldag raises and processes catfish for the local market. It is an end-to-end operation. A hatchery produces the fish eggs while the fingerlings grow into juvenile fish. In two large growout systems, the catfish feast on corn meal, reaching up to one kilo in weight.

Once the catfish are harvested, they are immediately smoked and slid into brightly colored packaging for sale in supermarkets around Nigeria.

Given the dense population of the fish in the tanks, the water quality can deteriorate quickly. This is because the catfish drain the oxygen and excrete ammonia, leading to toxic build up in the ponds. The water needs to be vigilantly aerated and cleaned.

To keep the fish alive, Shaldag uses a Recirculating Aquaculture Systems (RAS) — a technologically advanced system that maintains an ecological equilibrium between the flow of nutrients from the fish and the “good” nitrifying bacteria which converts it. It’s a complex living system that needs constant stability and minimum to no stress.

Running one of the largest RAS farms in West Africa, Shaldag consumes a lot of electricity. The company needs constant power to run the pumps, filters and blowers which clean and recycle the water.

The whole system ran on two brand new 250kVA generators in rotation and a smaller generator (50kVA) to power the office. Over time, the limitations of the generators as the primary power source became apparent.

Running 24/7, Shaldag’s generators racked up significant run hours. Although the three machines had a 10,000 hour lifespan, they approached 20,000 and the smaller one 30,000 hours in only four years. Given the constant wear and tear on the generators, Shaldag had to overhaul them — sooner as opposed to later.

While regular maintenance is par for the course with any machinery, overhauling a generator is serious. The engine, alternator, pumps, or other key components have to be replaced; it is like a heart transplant for a generator.

Just like a major operation needs an experienced surgeon, a rehauling needs a talented mechanic. The large generator manufacturers will dispatch their staff to repair their clients’ machines for a hefty price tag. For young businesses with limited capital, they will often save money on refurbishment, turning to a less experienced mechanic.

As generators are overhauled, their capacity to power the full load — i.e. the total consumption — can go down by as much as 20%. It’s a double whammy for Nigerian businesses: they pay full price for diesel but receive less electricity over time.

In the case of Shaldag, their two 250kVA generators kept breaking down. They had to frequently do repairs and change parts. Running 24/7 to power the farm’s equipment, the aging generators only further declined.

Not only did the generators stymy Shaldag’s ability to expand, they posed an existential threat to the fish farm. Even short power cuts can put the fish at risk. Without power to circulate the water, the water quality immediately starts to deteriorate. Ammonia and CO2 build up. Oxygen drops, stressing the fish and biofilter. They can even die.

A one-hour power cut and Shaldag starts losing hundreds of tons of catfish and ultimately the business.

The Shaky Grid: When 90% “Uptime” isn’t Good Enough

On the surface, many companies, especially in Lagos, are luckier than Shaldag. They receive some grid power. Whenever the grid power switches back on, it shrieks emitting a shrill noise in many Lagos neighborhoods. It signals to companies that they can shut off their diesel generators and for a moment save on power costs.

But, it isn’t what it appears to be. Businesses which receive grid power are ultimately in the same boat as off-grid companies. Nigeria’s grid is unreliable. Over a nine-year period, from 2010 to 2019, the national grid collapsed 206 times. (This is a conservative estimate since it doesn’t include when the distribution companies (Discos) switch off.)

Uptime — a consistent and uninterrupted power supply — is sacrosanct for many industries. Factories cannot take the risk of prolonged power cuts due to the electricity requirements of their production processes. Industries like aquaculture, dairy, or pharmaceuticals, to name a few, need a constant 24/7 flow of power. Otherwise, they simply aren’t viable.

Given the shaky grid, businesses that need 24/7 power have to run a backup diesel generator, which eliminates any savings from grid power. For many heavy duty industrial businesses, 90% uptime might as well mean 0% uptime. The resulting high energy costs make a business unattractive and deter foreign investors.

In 2011, a large Chinese glass manufacturer arrived in Lagos to explore setting up a glass factory in Ogun State. The erratic power supply immediately made it a non-starter. At the outset of the manufacturing process, the glass is liquid. If a power cut lasts longer than thirty minutes, the liquid glass solidifies, making it worthless. To start a new batch, the factory has to blow up the molten glass with dynamite which is not exactly a seamless process.

Glass manufacturing is already an incredibly energy intensive process. Furnaces that melt the raw materials into glass gobble large amounts of electricity. Glass manufacturers, like the Chinese producer that ventured into Nigeria, cannot afford to run backup generators to hedge against regular grid outages.

The company ultimately nixed its plans to build a glass factory in Nigeria.

Unpredictable Voltage: When Companies Voluntarily Disconnect from the Grid to Save their Equipment

Erratic voltage is the other bugaboo in Nigeria’s power sector. Nigeria’s standard voltage is 230V and 50Hz, but it rarely stays that stable. Voltage surges are common. Low voltage levels inflict even more damage. While businesses can deal with 200V, as soon as voltage dips under the 180–190V threshold, they face problems. In Nigeria, the voltage frequently plummets to as low as 150–170V.

The unpredictable jumps in voltage wreak havoc on production machinery, appliances, and critical components that regular power systems like inverters. It forces businesses and manufacturers alike to make another hard decision. They have to choose between cheaper grid power and the risk of ruining expensive machinery. Many businesses won’t take the risk and voluntarily disconnect from the grid.

Many large manufacturers in Agbara, Ogun State refuse to play Russian roulette with their machinery. Both global pharmaceutical company, GSK, and Swiss consumer goods company, Nestle, permanently disconnected from the grid to protect their equipment.

But, poor power quality isn’t just a headache for industrial businesses. Small ones are affected too. In Idiroko, on the Benin-Nigeria border, the local branch of Access Bank (one of Nigeria’s top three lenders) is a hive of activity. Cross-border traders stream into the bank, depositing wads of cash. Men and women wait in a line of chairs, shuffling from one chair to another as the teller calls “Next.”

As the bank can quickly feel stuffy with so much foot traffic, the branch manager had placed three 5 horsepower standing ACs that blasted cold air into the lobby. But, whenever the branch switched over to grid power, low voltage would trip the ACs. The air was so thick with humidity it could have been cut with a knife. The situation became unbearable for both branch staff and customers who, on a busy day, can wait for hours to make a transaction.

After facing issues with the faulty ACs, the bank branch finally disconnected from the grid.

A Quiet Revolution is Shaking up Nigeria’s Power Sector

For decades, Nigerian business owners have had to grapple with electricity scarcity.

Diesel procurement, generator breakdowns, and a finicky grid: it was simply the reality of doing business in Nigeria. But, over the last five years, Nigeria’s power sector — historically resistant to change — is seeing a quiet revolution.

Renewable energy is expanding rapidly in Nigeria. In particular, an increasing number of business owners are turning to solar power. Not only is solar affordable — the cost of solar energy has dropped an astounding 82% over the last eleven years— it is becoming more energy intense and efficient. When Nigerian businesses use solar with battery storage, which carries excess power for use when the sun isn’t shining, they’re able to reduce their diesel generator use by up to 40%.

In a second development, new energy service providers have popped up to take power supply management off of Nigerian businesses’ plates. For Nigerian business owners, weary of fiddling with generators, this is nothing short of a game changer. They can outsource their self-generation to third parties which act like utilities. Businesses flip on a switch and can expect to have light. That allows them to finally focus on their business.

For Shaldag, it was a relief to no longer worry about erratic power supply and maintenance. Nimrod Lazarus, Shaldag’s General Manager said, “Like in nature, a healthy ecological system can’t sustain too much stress. The stability of such a mechanized system needs a stable power supply. Otherwise we face a catastrophic risk’.

“We handed off our power production to a reliable and experienced third party. We can finally focus on our core business: producing healthy, happy fish.”